Rublev Colours Violet Hematite is a deep reddish purple hue that creates tints toward subtle violets when mixed with white. It is helpful in flesh tints and shadows, and its purple bias makes good grays. Rublev Colours Violet Hematite is formulated using pure natural ground hematite (Colour Index Name Pigment Red 102 or PR 102) that is absolutely lightfast and very opaque. This beautiful earthy red violet is cooler than other red iron oxide earths, such as Venetian red or Sartorius red.

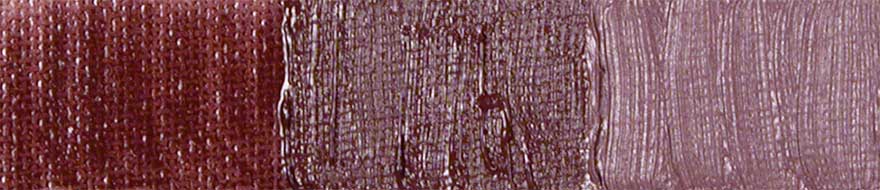

Color swatch of Rublev Colours Violet Hematite Artists’ Oil depicted thinly and thickly painted and tinted with equal parts of lead white.

Every pigment can yield two distinct hues, whether painted transparently or solidly mixed with white. The effect of using Violet Hematite painted thinly transparent and in solid color extends the range of hues accessible with it. Try rubbing a little Violet Hematite on a white surface, mixed with oil or a painting medium sufficiently thinned to show the white surface through it. You get a purple lake hue. Now, take the same color, mix a little white paint with it, and paint it solidly across the thin paint. It is quite a different color. The shift is more dramatic in Violet Hematite than in many other colors. The explanation for these color differences was observed by Harold Speed (1987), ‘All colors are made warmer when painted over light grounds transparently, and all colors are made colder when mixed with white.’

Rublev Colours Violet Hematite is ground in linseed oil without using any stearates, wax, or other additives that affect the behavior of the pigment in oil. The pale linseed oil used to make this color is well-aged and refined to provide higher levels of reactivity and oxidation than raw oil. The consistency is a smooth, thick, rich color that brushes ‘long’ [1] yet holds its shape remarkably well. When the color is brushed out, it readily flows under the brush but remains in place, staying put when lifted.

About the Pigment

| Group | Iron oxides and hydroxides |

| Subgroup | Hematite, Iron(III) oxide |

| Synonyms | Caput mortuum, mineral purple, purple ocher, Mars violet |

| Specific Gravity | 5 (water =1) |

| Oil Absorption | 100 g pigment / 18 g oil |

Hematite is the mineral form of iron(III) oxide and the principal colorant in red, brown, and purple iron oxide-based pigments, both natural and synthetic. Hematite is a significant source of iron oxide earth pigments and a component of ocher, umber, and sienna colors. The mineral is found in many places throughout the earth, a primary source of the pigment from soft, red, earthy masses of hematite called ‘paint ore.’

Hematite mineral specimen from ‘paint ore.’

The iron content (as Fe2O3) of the pigment used in Rublev Colours Violet Hematite is 98 percent. It is a heavy mineral, having a specific gravity of 5 (water, for example, has a specific gravity of 1). With a mean particle size of 1.8 microns and high density, it has very low oil absorption (15 grams of oil for 100 grams of pigment), which means that it requires very little oil to make a medium stiff paste paint, making it a very lean color.

What is unusual about the pigment used in Rublev Colours Violet Hematite is the micaceous structure of its particles. Hematite is most often found in crystalline form but more rarely as micaceous hematite (also called specular hematite or specularite), consisting of very thin leaves of iron ore with the metallic luster of polished iron. These small, hexagonal plates produce a glistening effect, giving the paint a metallic sheen (Schmelzer, 1976). This effect, known as ‘bronzing,’ gives Rublev Colours Violet Hematite a metallic cast that appears on the surface of pure and densely applied paint.

The color of hematite, which can range from yellowish red to cold tones of purplish red, depends on the particle size of the pigment. Helwig (1998) identified violet iron oxide colors as consisting of coarser particles of hematite than the red shades. Particles of size 0.1 to 0.2 microns appear bright red, whereas a blue-red to purple color is observed with a 1 to 5-micron grain size. In their paper, Oliveira et al. (2002) used Raman spectroscopy to characterize modern purple iron oxide pigments. They, too, noted the variation in color from these samples as related to the particle size of the pigment. Interestingly, this variation of color from red to purple can be observed in Rublev Colours Violet Hematite during grinding and brushing the color out thinly.

History of the Color

The word hematite is derived from the Greek word haima, referring to blood, undoubtedly due to its red color. The use of this mineral as a pigment is one of the earliest in humankind’s history. Theophrastus’ On Stones (c. 315 B.C.E.) is the earliest known reference to what is thought to be hematite; his name for the material, which translates as bloodstone, was based on its blood-red appearance. Some four hundred years later, Pliny the Elder (c. 77 C.E., Book xxxvii) used hæmatite, the Latin equivalent, in his widely cited Historia Naturalis.

Recent analyses of purple iron oxide colors described in several papers (Bikiaris et al., 1999; Daniila et al., 2002; Oliveira et al., 2002) show that hematite-rich pigments were used in Roman, Byzantine, and post-Byzantine art.

James Ward (1915) and Arthur Pillans Laurie (1949) argue that the sinopia and cinabrese described by Cennino Cennini in his 15th-century painting treatise must have been varieties of hematite, which Ward describes as ‘similar, if not the same substance as that which is now known as Indian or Persian red.’ He goes on to describe the qualities of the hematite variety known as ‘Indian red,’ a purplish red iron oxide: “the quality and properties of the finest and purest Indian red, and its beautiful tints when mixed with lime-white, which have the appearance of delicate lake tints, are exactly such as he describes when sinopia and cinabrese are mixed with bianco sangiovanni (lime-white).”

Several sixteenth-century authors cited by Mary Merrifield in The Art of Fresco Painting (1846) describe a pigment known variously as lapis amatita (Baldinucci), lapis amatito (Borghini), amatita, matita rossa (Palomino), and albin (Pacheco), which she convincingly argues refers to hematite.

Chamber’s Cyclopedia (1738) states that a purple hematite called ‘Indian red’ was ‘brought from the island of Ormus in the Persian Gulf.’ However, in The Handmaid to the Arts, Robert Dossie (1764) states that this color was prepared from caput mortuum, an artificially prepared pigment made by the aqueous precipitation of iron salts with alkalis, which are then roasted to produce dark purple shades of iron(III) oxides. George Field in Chromatography (1835) describes purple ocher as a native ocher from the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. However, in the 1841 edition of his book, he notes that it can be prepared artificially by calcining natural red ocher and ‘has been employed under the denomination of Violet de Mars.’

Notes

1. Long refers to the consistency of paint that displays tall peaks when a palette knife is pressed to its surface and lifted. Long paint is also described as “ropy” and refers to a stringy quality, like honey. Paint that behaves in this way is said to have long rheology. Short rheology refers to paint with a more buttery consistency, which is typical of most commercial oil paint. Rheology studies how substances flow, such as liquids and soft solids, that flow rather than deform elastically.

References

(Bikiaris et al., 1999) Bikiaris, D.; Daniila, Sr.; Sotiropoulou, S.; Katsimbiri, O.; Pavlidou, E.; Moutsatsou, A.P.; Chryssoulakis, Y.’ Ochre-differentiation through micro-Raman and micro-FTR spectroscopies: application on wall paintings at Meteora and Mount Athos, Greece,’ Spectrochemica Acta, Part A 56 (1999) p. 3–18.

(Chambers, 1738) Chambers, E. Cyclopaedia: A Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. Midwinter, London (1738).

(Daniila et al., 2002) Daniila, Sr.; Bikiaris, D.; Burgio, L.; Gavala, P.; Clark, R.J.H.; Chryssoulakis, Y. ‘An extensive non-destructive and micro-spectroscopic study of two post-Byzantine overpainted icons of the 16th Century,’ Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 33 (2002) p. 807–814.

(Dossie, 1764) Dossie, Robert. Handmaid to the Arts, 2nd ed. London, 1764.

(Field, 1835) Field, George. Chromatography: or a Treatise on Colours and Pigments, and of their Powers in Painting. Charles Tilt, London, 1835.

(Field, 1841) Field, George. Chromatography: or a Treatise on Colours and Pigments, and of their Powers in Painting. Tilt and Bogue, London, 1841.

(Helwig, 1998) Helwig, Kate. ‘Mars colours: preparation methods and chemical composition,’ Painting Techniques History, Materials, and Studio Practice, Summaries of Posters at the I.I.C. Dublin Congress, 7-11 September 1998 I.I.C., London, 1998.

(Laurie, 1949) Laurie, Arthur Pillans. The Technique of the Great Painters. Carroll and Nicholson, 1949. p. 63.

(Merrifield, 1846) Merrifield, Mary P. The Art of Fresco Painting: As Practiced by the Old Italian and Spanish Masters. Charles Gilpin and Arthur Wallis, London, 1846.

(Oliveira et al., 2002) de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Edwards, H.G.M.; Frost, R.L.; Kloprogge, T.; Middleton, P.S. ‘Caput mortuum: spectroscopic and structural studies of an ancient pigment,’ The Analyst 127 (2002) p. 536–541.

(Sikong et al., 2001) Sikong, Lek; Pongramun, Thitipun; Phunmuang, Natsima. ‘Fine grinding of hematite for making pigment,’ Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2001). p. 391–397.

(Schmelzer, 1976) Schmelzer, H. XIII Congress FATIPEC (Fédération d'Associations de Techniciens des Industries des Peintures, Vernis, Emaux et Encres d'Imprimerie de l'Europe Continentale), Cannes, Juan les Pins 1976, Congress book, p. 573–574.

(Speed, 1987) Speed, Harold. Oil Painting Techniques and Materials. Dover Publications, New York, 1987. p. 118.

(Ward, 1915) Ward, James. History and Methods of Ancient and Modern Painting. Dutton, 1914. p. 184–185.

Rublev Colours Violet Hematite

Although Violet Mars oil colors based on synthetic iron oxide can be found among the colors made by other artists’ paint manufacturers, Natural Pigments introduces the only natural purple iron oxide oil color with micaceous particles in Rublev Colours, Violet Hematite.

Rublev Colours Violet Hematite Pigment

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names: | English: red oxide French: oxyde rouge German: Oxid rot Italian: rosso ossido Portuguese: vermelho óxido Spanish: rojo óxido |

||||||

| Alternate Names: | Mars Violet is the name given to the artificial substitute of natural violet red iron oxide. | ||||||

| Nomenclature: |

|

||||||

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Red |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Red 102 (77491) |

| Chemical Name: | Iron Oxide |

| Chemical Formula: | Fe2O3 |

| ASTM Lightfastness Rating | |

| Acrylic: | I |

| Oil: | I |

| Watercolor: | I |

| Properties | |

| Specific Gravity: | 5.0 |

| Hardness: | 5.0–6.0 |

| Refractive Index: | 2.78–3.01 |

| Oil Absorption: | 18 g / 100 g |

Rublev Colours Violet Hematite Artist Oil

| Color Information | |

| Single Pigment: | Violet Hematite |

| Binder: | Linseed Oil |

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Purplish Red |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Red 102 (77491) |

| Chemical Name: | Iron Oxide |

| Chemical Formula: | Fe2O3 |

| Properties | |

| ASTM Lightfastness: | I |

| Opacity: | Opaque |

| Tinting Strength: | High |

| Drying rate: | Above Average |

| Health Label: | Based on a toxicological review, there are no acute or known chronic health hazards with the anticipated use of this product. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and concentrated vapors. Contact us for further information or consult the MSDS for more information. |

Where to Buy

Shop for

Shop for

Shop for

Shop for

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary hue of Violet Hematite?

Violet Hematite is a deep reddish-purple shade.

How does the color shift when mixed with white?

When mixed with white, Rublev Colours Violet Hematite tints towards subtle violets. Lead white produces warmer reddish violets, while titanium white produces colder violet hues.

What makes Violet Hematite unique when painted transparently and solidly mixed with white?

Violet Hematite has a remarkable shift in hue when painted transparently compared to when solidly mixed with white. When painted thinly and transparently, it achieves a purple lake hue, while mixing with white paint brings out a different, cooler hue.

How is Rublev Colours Violet Hematite formulated?

It is formulated using pure natural hematite (PR 102 or Pigment Red 102) ground in linseed oil without the use of stearates, wax, or other additives.

What unique characteristic does the Rublev Colours Violet Hematite have due to its mineral source?

The pigment is based on hematite, which is the mineral form of iron(III) oxide and a principal colorant in various iron oxide-based pigments. The micaceous structure of this hematite pigment gives the paint a unique metallic sheen, known as 'bronzing,' which is evident on the surface of pure and densely applied paint.

What is the historical significance of hematite as a pigment?

Hematite, derived from the Greek word "haima" meaning blood, has been used as a pigment since ancient times. It has been mentioned in texts such as Theophrastus' On Stones from 315 B.C.E., Pliny the Elder's Historia Naturalis, and was prevalent in Roman, Byzantine, and post-Byzantine art.

Which artists and authors have mentioned or used hematite in their works?

Historical figures like Theophrastus, Pliny the Elder, Cennino Cennini, James Ward, and Arthur Pillans Laurie have either mentioned or utilized hematite. It's also cited in various publications, from ancient texts to sixteenth-century writings, highlighting its rich history and prominence in the art world.

Is Violet Hematite a natural or synthetic pigment?

Violet Hematite is pure natural ground hematite.