Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, or Raphael, was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired worldwide for its form, composition, and visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of the human form.

The Painting Materials of Raphael

Raphael painted much of his early works on poplar wood panels but, in some cases, on a much denser fruitwood. For example, Madonna of the Pinks appears to be painted on a panel of cherry wood. More unusual is the portrait of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni painted on limewood. There is also a rare early example of a poplar panel covered with canvas. This processional banner, a double-sided gonfalone, of The Trinity with Saints Sebastian and Roch on one side and The Creation of Eve on the other, is exceptional, but the choice can be explained by its use as a banner carried at religious festivals.

The Madonna of the Pinks ('La Madonna dei Garofani'), National Gallery, London, was made about 1506–7, using oil on yew (Taxus baccata) panel.

Even later in his career, Raphael rarely chose canvas as support. the principal exception being the Sistine Madonna.

Most of the wood panels were prepared with a glue ground consisting of gypsum (calcium sulfate hemihydrate, gesso, Italian) bound in animal glue. The gesso was covered with a pale imprimatura of a thin, off-white oil-bound layer containing lead white, a small amount of lead-tin yellow, and various amounts of glass particles. It is believed that the glass particles contributed to the siccative qualities of the imprimatura. The composition of this imprimatura has been found in many of his paintings and appears to be typical of Italian artists working in this period.

Mediums Used by Raphael in His Paintings

Raphael's exposure to a diverse array of techniques was significantly shaped by his early experiences in Giovanni Santi's workshop and later in Perugino's. These environments were known for producing artworks on both panel and canvas, varying in size and utilizing a spectrum of media. This included egg tempera, oil paints, hybrid mixtures of egg and oil, glue tempera on canvas (known as distemper), and buon fresco techniques.

In the late fifteenth century, Raphael extensively experimented with egg and oil mixtures on panel surfaces. Noteworthy practices included the application of egg tempera with minimal quantities of drying oil, known as tempera grassa, the strategic layering of oil glazes atop egg tempera underpaintings to enhance the vibrancy and transparency of red lakes, copper-based greens, and ultramarine blue, and the selective use of egg for certain pigments and passages while reserving drying oil for others.

Raphael predominately used drying oils in his work, mostly consisting of walnut oil but also accompanied by linseed oil. Spectrophotometry analysis has revealed walnut oil and linseed oil in separate passages of paintings, such as Saint Catherine and Mond Crucifixion. In samples analyzed from the Ansidei Madonna, walnut oil and heat-bodied walnut oil were detected. Three samples from the Madonna of the Pinks contained heat-bodied walnut oil. Walnut oil appears to be the preferred binder in Italy during this period, although linseed oil was used. In some cases, these oils were used in separate passages of paintings.

Of course, egg tempera cannot be dismissed as a binder used by Raphael because this was often employed in Pietro Perugino's workshop, where Raphael apprenticed.

The main panel from the Ansidei Altarpiece, Ansidei Madonna, National Gallery, London, is dated 1505 and inscribed in gold on the hem of the Virgin’s mantle.

Techniques of Composition and Application

Raphael's approach to constructing foregrounds, backgrounds, and skies typically involved using wide, horizontal brushstrokes, occasionally leaving visible brush marks and imparting a slight texture to the surfaces. Central compositional elements, including figures, were initially left unpainted. The background coloration was subsequently added around these unpainted areas, either by extending the horizontal brushstrokes to meet these zones or by delicately painting around the figures' contours. Instances, such as in the Mond Crucifixion, reveal areas where the paint from both the figures and the landscape does not fully obscure the underpainting, allowing the imprimatura to remain visible, indicative of a meticulous and thoughtful layering process.

In larger compositions, Raphael demonstrated a propensity for executing expansive passages with fluid, free brushwork in singular layers of oil paint, showcasing his mastery over the medium.

Achieving Color Saturation

Raphael's technique for achieving specific color saturation or when the nature of certain pigments demanded a layered approach was particularly evident in the nuanced green, red, and subdued pink draperies within the Mond Crucifixion. This involved the application of glaze-like surface paints over solid, color-matched underlayers. The dense application of paint in areas such as the green sleeve and yellow lining of draperies in Saint Catherine exemplifies Raphael's method of building color depth through the use of copper green glazes atop opaque layers of verdigris mixed with white or lead-tin yellow and the creation of translucent reds through the application of red lake glazes over a base of vermilion or a mixture of vermilion with white, red earth, or lake.

Development of Blue Colors

The specific technique for blues involved the layering of natural ultramarine over azurite or a mixture of azurite with white, resulting in a notably thicker layer of paint, a practice observable in the Ansidei Madonna and the Madonna of the Pinks.

Modeling of Flesh Tones

Raphael's early period flesh tone modeling closely mirrored the practices of the Perugino workshop and drew upon techniques developed by Verrocchio and his disciples. This often involved using a greenish-brown underpainting, potentially evolving from the traditional green earth underpainting of earlier panel paintings, and further modeled with a brownish-green verdaccio comprising translucent yellow pigments and black. Applying thin layers of flesh-colored paint, followed by adding opaque pinkish or brownish-pink layers for highlights, over a semi-translucent, greenish-brown underpainting, allowed for the representation of shadows through the exposed lower layer.

The Palette of Raphael

Raphael's core palette in his early works featured azurite, ultramarine, verdigris, copper green glazes, lead-tin yellow (Type 1), vermilion, red lake, yellow lake, earth pigments, carbon blacks, and lead white. Advanced analytical techniques have unveiled the inclusion of previously undetected or uncharacterized materials such as red lead, orpiment, and a unique dark, warm grey pigment derived from metallic bismuth in his compositions, expanding our understanding of his material choices beyond the traditional canon of the Quattrocento and early Cinquecento periods.

Raphael used many pigments typically found in paintings of this period. These included the following:

-

Natural ultramarine (lazurite mineral)

-

Verdigris (copper acetate)

-

Yellow ocher (iron oxide)

-

Lead-tin yellow (lead stannate—Type I)

-

Carmine lake (carminic acid precipitated on a mineral base)

-

Vermilion (red mercuric sulfide)

-

Madder lake (alizarin, pseudopurpurin, and purpurin on a mineral base)

-

Red ocher (iron oxide)

-

Brown ocher (iron oxide)

In several of his paintings (Ansidei Madonna), he employed the rare Brazilwood lake, shell gold, and even less-known metallic powdered bismuth.

One of the two narrative scenes from the predella of the Ansidei Altarpiece, Saint John the Baptist Preaching, National Gallery, London, is dated 1505 and inscribed in gold on the hem of the Virgin’s mantle of the main panel of the altarpiece.

Raphael's Use of Glass Powder

Analyses have revealed the presence of colorless glass particles within the imprimatura and various paint layers of certain artworks, notably those featuring red lake pigments. It has been determined that this glass was incorporated as a drying agent, a function elaborated upon in the context of the Ansidei Madonna. Investigation into the composition of these glass particles has consistently identified manganese as a constituent, affirming its role as a desiccant. The use of glass for this purpose extends beyond Raphael's oeuvre, marking a prevalent practice among sixteenth-century painters. Nonetheless, Raphael's application of this technique was notably prolific. When combined with opaque pigments, this addition of glass notably enhances the translucency of the paint, a distinctive characteristic of Raphael’s painting technique.

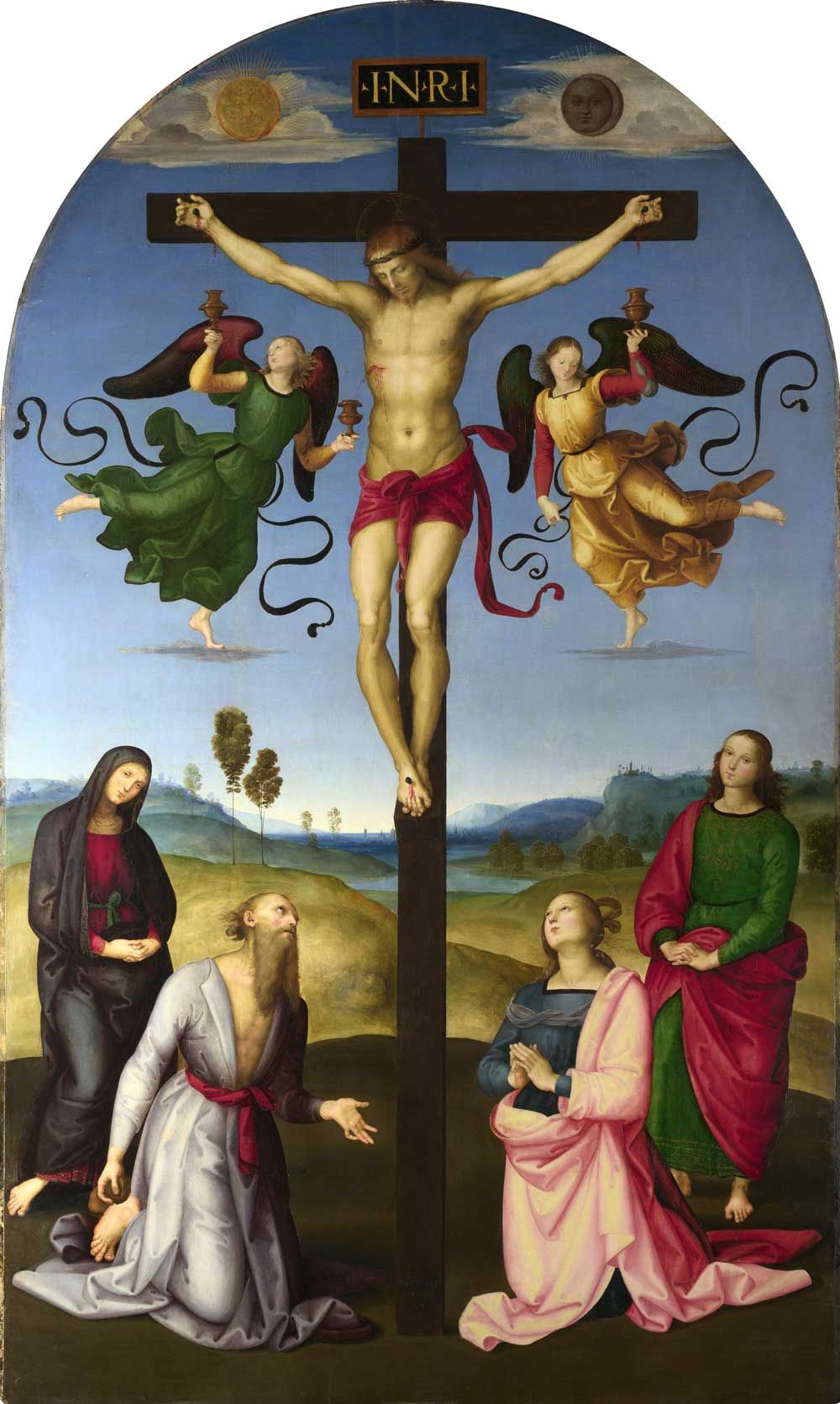

In the Mond Crucifixion, Raphael prepared the poplar support with gesso covered by an imprimatura of lead white, a small amount of lead-tin yellow, and powdered glass consisting of manganese-containing soda-lime glass. Considerable amounts of powdered glass were also found in the red glazes of Saint John the Evangelist’s cloak. Powdered glass was also added to many other areas of the painting, not just in the red glazes. The use of this type of glass not only acts as a siccative but increases the transparency of the glazes while providing solid particles that do not yellow, as does the oil binder.

The use of glass as a siccative in oil painting is consistent with an English documentary source that mentions using glass as a drier. The painter Marshall Smith, in 1692, wrote:

‘For your Powder-Glass, take the whitest Glass, beat it very fine in a Morter, and grind it in water to an Impalpable powder; being thoroughly dry, it will dry all Colours without drying Oyle, and not in the least Tinge the purest Colours, as White, Ultramarine etc. and is much us’d in Italy’.

The Mond Crucifixion, National Gallery, London, was painted in oil on a poplar panel about 1502–3.

Glass particles have also been found extensively in works by Perugino and in many paintings by Raphael. Recently, it has been found that glass was used extensively in red glazes in early Netherlandish and German paintings. The composition of the glass varies considerably in the paintings from different regions of Europe during this period. Soda lime glass is typically found in Italian paintings, but high-lime glass appears to be more common in paintings executed in Northern Europe.

Shell Gold and Gilding

The final step in the painting process involved applying either shell gold or mordant gilding to embellish various elements, such as the gold thread motifs and designs adorning the necklines and edges of the draperies on several figures. Additionally, details like haloes were frequently rendered using shell gold. Notably, in the Ansidei Madonna, the lower edge of Saint John the Baptist's vibrant red cloak features a layer of shell gold, enhanced by an additional layer of metallic silver, though the visual effect has diminished due to metal degradation.

The use of mordants in the gilding process varied, with some being thick while others were more lightly applied. The Ansidei Madonna contains examples of mordant gilding in the throne's inscribed overlay, the gilded Greek key motifs on the canopy and base, and the golden orbs near Saint Nicholas of Bari's feet. The 'INRI' inscription on the Mond Crucifixion's cross was also applied with mordant gilding directly onto the imprimatura, with adjacent paint meticulously avoiding the gilded text.

Raphael's signature, uniquely placed at the cross's base, is presented in a sgraffito technique, created by etching through the semi-wet brown paint to unveil a layer of silver leaf beneath. The moon, positioned at the Crucifixion's upper right, was depicted using tarnished silver leaf, contrasting with the gold leaf used for the sun, both applied atop a red-brown bole layer employing the traditional water gilding method.

The sun, located at the painting's upper left, and the similarly crafted silver moon on the upper right were both produced through water gilding, with gold and silver leaf laid over red bole. The application of gold on finer details, such as Christ's loincloth, the angels' wings, Saint Jerome's belt, and the edges of the Virgin and Saint John's robes, remains ambiguous. However, the absence of colored mordant and the distinctiveness of the lines probably indicate the probable use of shell gold despite appearing denser than typically seen for shell gold. The gilded decoration on Saint John's green cloak appears to be gold in flake form, not as a continuous gold leaf layer, suggesting the use of shell gold. This application was more robust than typically associated with shell gold but resembled the gilding on Saint John's robe in the Ansidei Madonna, affirming its identification as shell gold. Another possible explanation is "gold assiste," which relies on applying gold skewings applied onto a mordant, usually a water-based size.

The detail view of the Ansidei Madonna shows shell gold and silver on the hem of the cloak.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the sfumato technique?

The sfumato technique, often associated with Leonardo da Vinci, involves blending colors and tones to achieve a soft, gradual transition between shades, especially in areas where light and shadow meet. This technique creates a smokey, realistic effect, enhancing the three-dimensional appearance of the subject.

What was Raphael's personality like?

Raphael was known for his charming and gracious personality. His contemporaries often described him as kind, generous, and approachable, qualities that endeared him to patrons and peers alike. His disposition contributed significantly to his success as an artist and his ability to collaborate effectively with others.

What is Raphael's most famous painting called?

Raphael's most famous painting is arguably "The School of Athens," a masterpiece of the High Renaissance that represents philosophy. Located in the Vatican's Apostolic Palace, this fresco showcases a gathering of ancient Greek philosophers in an idealized architectural setting, embodying the spirit of the Renaissance.

Who taught Raphael to paint?

Raphael was initially trained by his father, Giovanni Santi, a painter at the court of Urbino. After his father's death, Raphael continued his apprenticeship with the Umbrian master Pietro Perugino. Perugino's influence is evident in Raphael's early works, which share the master's clarity of form and precise treatment of detail.

References and Notes

Bomford, D.; J. Dunkerton, D. Gordon and A. Roy (1989). Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400, exhibit catalog, National Gallery, London 1989, p. 29 and catalog entries; Dunkerton and Roy 1996 (cited in note 32).

Buzzegoli, E.; D. Kunzelman, C. Giovannini, G. Lanterna, F. Petrone, A. Ramat, O. Sartiani, P. Ivioioli, and C. Seccaroni (2000). ‘The use of dark pigments in Fra Bartolommeo’s paintings,’ Art et Chemie, la couleur. Actes du Congres, Paris 2000, pp. 203–8.

Dunkerton, J. and A. Roy, A. (1996). ‘The Materials of a Group of Late Fifteenth Century Florentine Panel Paintings,’ National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 17, pp. 21–3l.

Kirby, J. and White, R. (1996). ‘The Identification of Red Lake Pigment Dyestuffs and a Discussion of their Use,’ National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 17, 1996, pp. 56–80.

Roy, A., Spring, M., Plazzotta, C. “Raphael’s Early Work in the National Gallery: Paintings before Rome”. National Gallery Technical Bulletin Vol 25, pp. 4–35.

Spring, Marika. “Raphael’s Materials: Some New Discoveries and their Context within Early Sixteenth-Century Painting.” Scientific Department of The National Gallery, London

References to the use of powdered glass as a drier in historical documentary sources on painting are discussed, and Marshall Smith is quoted in Kirby Talley M., Portrait Painting in England: Studies in the Technical Literature before 1700, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1981, pp. 94–97.

Spring, M.; R. Grout, and R. White (2003). ‘Black Earths: A study of Unusual Black and Dark Grey Pigments used by Artists in the Sixteenth Century,’ National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 24, 2003. pp. 96–114.